|

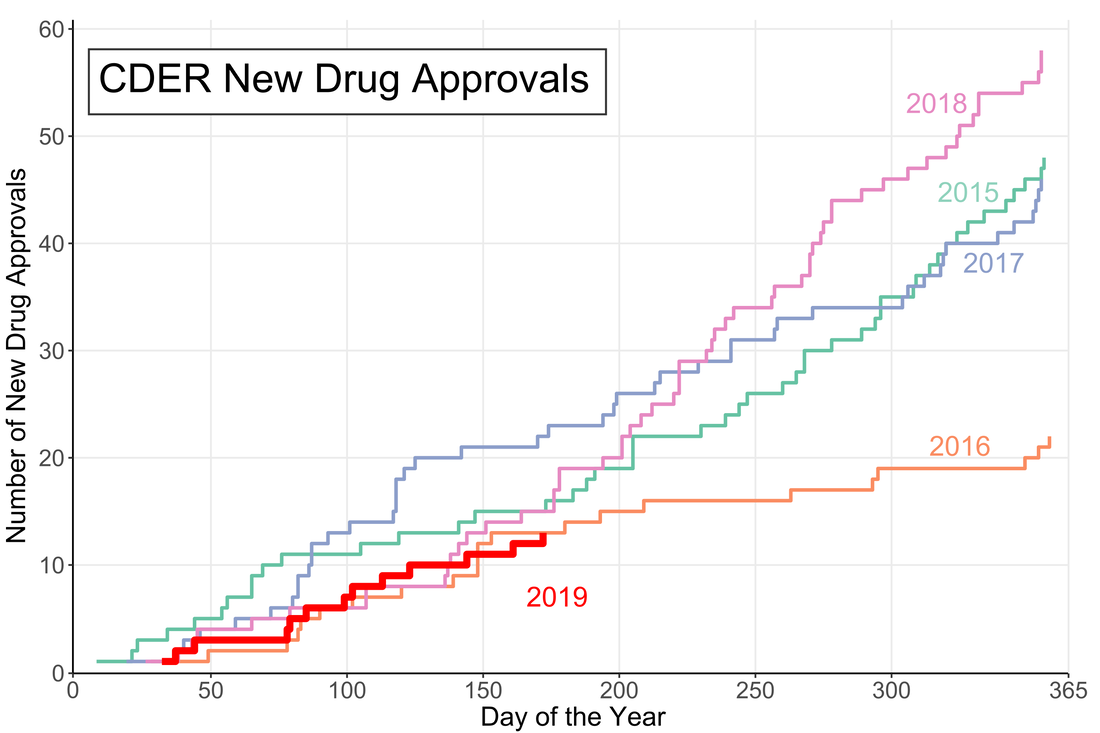

A little over halfway through the year and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) appears to be on track for either a big year of new drug approvals or....not. The number of new molecular entities (NMEs) approved by FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) are equal to the number approved at this point of the year in 2016 and only two product apporvals behind both 2018 and 2015. Despite starting the year off with the longest federal shutdown in history the FDA is keeping pace with past years.

However, the figure demonstrates another important fact: approval numbers mid-year do not correlate strongly with year-end approvals. While the number of approvals were similar in 2016 and 2018, the end year totals were wildly different. In 2018, CDER approved a record 59 NMEs while 2016 approved less than half of that number. Additionally, in 2017, the number of NME approvals at mid-year was much higher than any other year, but finished in line with the number of approvals in 2015 and well below the number of approvals in 2018. It seems that the future could go either way. There could be a dramatic up-tic in CDER approval rate as in 2018 (perhaps from shutdown-delayed applications) or the rate could slow to a crawl like in 2016.

0 Comments

Let’s say you want to buy a new car. Now, you aren’t a car expert, but you have a general idea of features you want in your slick new whip and you can find a market-determined price for the car you want online. Every day that your new car gets you from point A to point B without violently exploding you’ll know that you made a good decision. This is what cars are like.

Drugs are not like cars. Drugs are complicated little molecules pressed into tablets that a doctor tells you to take one, two, three times per day, maybe until you die. How much do drugs cost? They cost whatever your pharmacist says they cost. Drug prices are obscured both by a lack of patient drug expertise and the complex negotiations between insurers, manufacturers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and pharmacies. Because patients cannot easily find a price for a drug it is fair to ask if they are paying too much. Fear not! The government regulates drugs, pharmacies, AND insurance companies. The government recognizes that patients do not know a lot about drugs and steps in to protect them. In fact, one of President Trump’s campaign promises was to lower the out-of-pocket costs for drugs. To that end, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released American Patients First, (APF) Trump’s blueprint to lower drug prices. It’s essentially a series of hypothetical plans that could maybe lower the cost of prescriptions in the United States. The APF correctly points out that consumers asked to pay $50 vs. $10 are 4 times more likely to abandon their prescription at the pharmacy. We want patients to be able to afford their medications and to therefore be healthier. This is an important point to remember: reducing out-of-pocket costs is only useful if it increases health. Let’s see how the APF will make Americans healthier. First we need to understand the justification for this beautiful document. Why are drug prices high? Well one given reason is that the 1990s saw the release of several “blockbuster” drugs that dramatically increased pharmaceutical company revenues. However, many of these drugs lost patent protection in the mid-2000s. In order to maintain constant revenue streams, the APF posits, companies raised prices on other drugs. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) put upward pressure on drug prices in a few ways. First it increased the number of critical-need healthcare facilities that receive mandatory discounts on drugs (340B entities). It also placed taxes on branded prescription drug sales. This was implemented to shift patients and organizations away from using brand-name (read: expensive) drugs when generics are available. To pay these taxes however, drug costs had to go up. All of these justifications for high drug prices establish a pattern: if one person is paying less then the costs shift somewhere else. Someone has to pay. How does the APF plan propose to tackle high out-of-pocket costs? The strategies are presented as a four-point plan. First, it proposes that the US increase competition in pharmaceutical markets. Classic free market stuff right here. One part is a FDA regulatory change which prevents a company from blocking entry of generic competitors into the market. Seems like a straightforward good idea. The other noteworthy idea here is to change how a certain class of expensive injectable drugs, biologics, are billed. This would prevent “a race to the bottom” in biologic pricing which would make the market less attractive for generic competition. Essentially this rule could help keep biologic prices high, to make the market profitable, so there is generic competition, to lower prices. It is difficult to predict if this would work or not. The second objective is to improve government negotiation tools. This part is pretty fleshed out, with 9 different bullet points. However 8 of the 9 points relate to Medicaid or Medicare primarily helping old and/or poor people. Right now drug coverage by Medicare cannot take price into consideration when deciding whether to cover a drug. If the largest insurer in the country (the government) can start negotiating on prices, the market could shift dramatically. However someone has to pay and this may shift prices to private plans. Another goal in this section is the work with the commerce department to address the unfair disparity between drug prices in America and other countries. It is unclear how this would be achieved. The third objective is to create incentives for lower list prices. Drugs have many different prices based on who is paying on them. Companies may be incentivized to raise list prices to increase reimbursement rates since they often only receive a portion of the list price for a drug. However if the drug is not covered by a patient’s plan they could be on the hook for the inflated list price. One of the most widely criticized parts of the APF plan is to include list prices in direct-to-consumer advertising. Since most people do not pay the list price, is it even helpful to include? Probably not. The final objective is to bring down out-of-pocket costs. I thought this was the purpose of the whole document so I was surprised that it is also one of the sub-sections. Both of the proposals here target Medicare Part D, so they may have limited benefits to non-Medicare patients. One proposal is to block “gag clauses” that prevent pharmacies from telling patients when they could save money by not using insurance. While this will indeed lower out of pocket costs for certain prescriptions, the point of insurance is to spread out the costs. The inevitable side effect will be price increases in other prescriptions. The long final portion of the document is a topic by topic list of questions that need to be addressed. Who knew that healthcare was so complicated? There are some good ideas in here that need to be explored like indication-based pricing or outcomes-based contracts. Austin Frakt has a good piece on these here. My favorite question in the section is: “How and by whom should value be determined??” Yes the question in the APF includes the double question marks. This questions really gets to the philosophical crux of the healthcare problem. It should be pretty simple to solve. Here are some other quotes: “Should PBMs be obligated to act solely in the interest of the entity for whom they are managing pharmaceutical benefits?”

As of this writing, none of these policies have been implemented, but the President could instruct the FDA to begin them theoretically whenever. There are still many implications to these policies that are unknown. Each one likely has unintended consequences, as all policies do. The two critical questions we need to ask of our policy makers going forward are:

So uh good luck to us. |

Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed