|

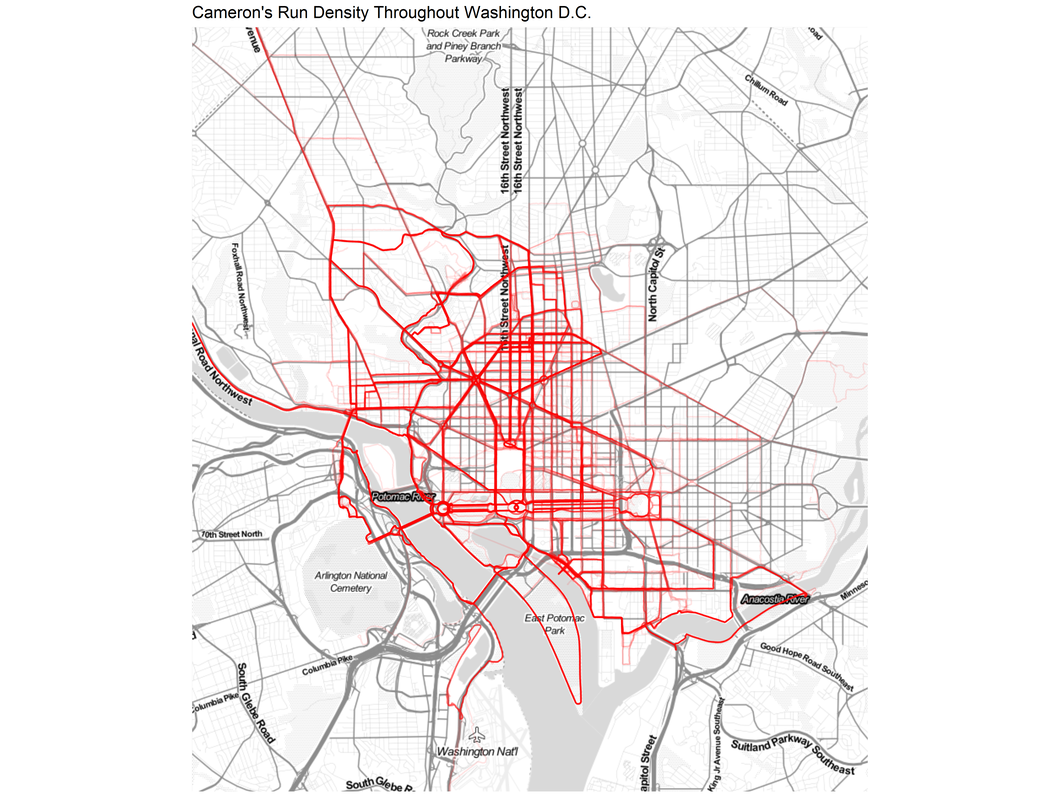

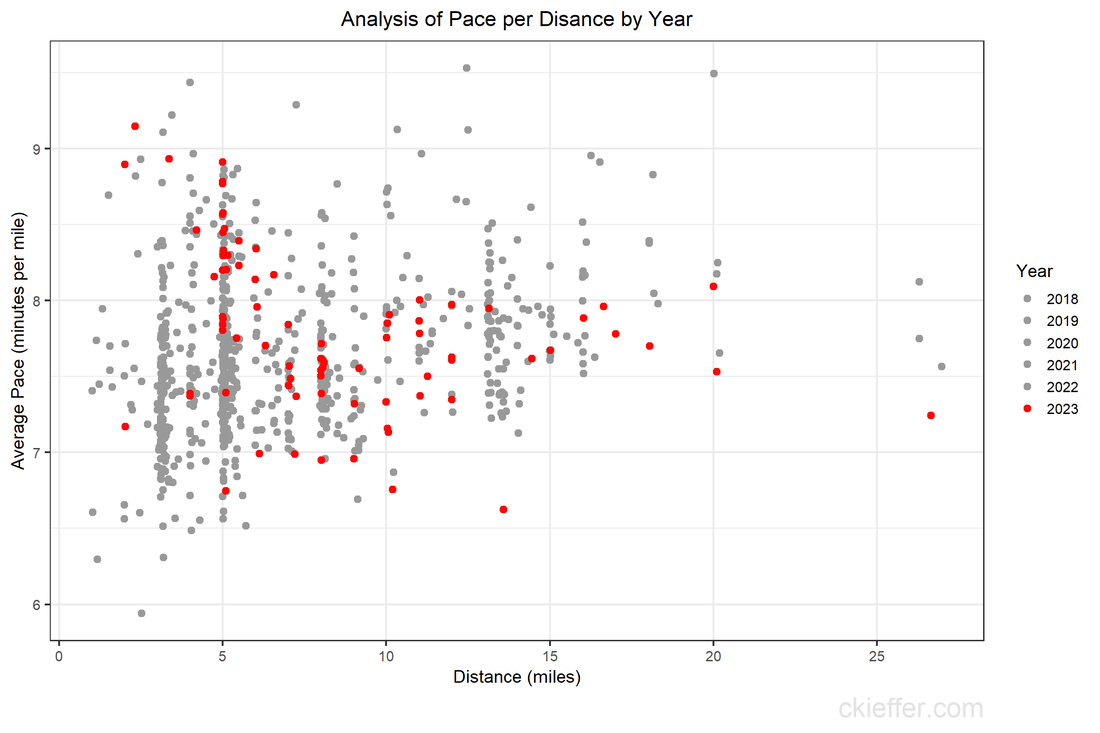

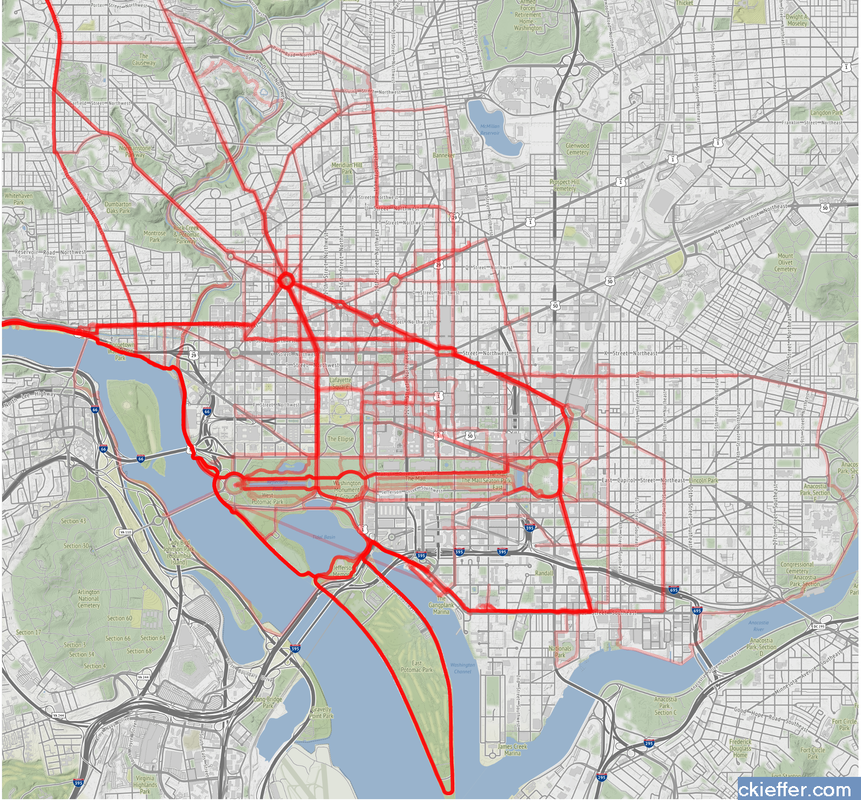

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, everyone was trapped indoors. Various jurisdictions had different policies on appropriate justifications for venturing outside. I vividly remember the DC National Guard being deployed to manage the flow of people into the nearby fish market. However, throughout the pandemic, outdoor and socially distant running or exercising was generally allowed. Because the gyms were closed and the outdoors were open, my miles run per week shot up dramatically. I even wrote a blog post about it in April 2020. Now the pandemic has subsided, but I the running has not. In fact, I’m running more than ever in a hunt for a Boston Marathon qualifying time. During this expanded training, and throughout the past three years, I have run many of the local DC streets. I have updated the running heatmap that I published in 2020 after several thousand additional miles in the District. I’ve been told the premium version of the Strava run tracking phone app will make a similar map for you. This data did come from Strava, but I’ve created my own map on the cheap using a pinch of guile (read: R and Excel). This version of the map features a larger geographic area to capture some of the more adventurous runs that I have taken to places like the National Arboretum, the C&O Trail, and down past DCA airport. The highest densities of runs are along the main streets around downtown, Dupont Circle, and the National Mall. Rosslyn and south of the airport were two areas that I wanted to explore more in my 2020 post, both of which show up in darker red on this new figure. To complement the geographic distribution of runs is a visual distribution of average pace vs. run distance. This was a challenge to analyze because the data and dates were downloaded in Spanish (don’t ask), but eventually I was able to plot each of the 798 (!) DC-based runs over the past five years. The runs in 2023 are highlighted in red. Luckily, the analysis reveals that many of the fastest runs for each distance are in the past 6 months. Progress! My rededication to running at a more relaxed pace for my five mile recovery runs is also visible. The next step is to fill in the space this figure with red dots for the rest of 2023 with the ultimate goal of placing a new dot in the bottom right corner by 2024. Wish me luck.

0 Comments

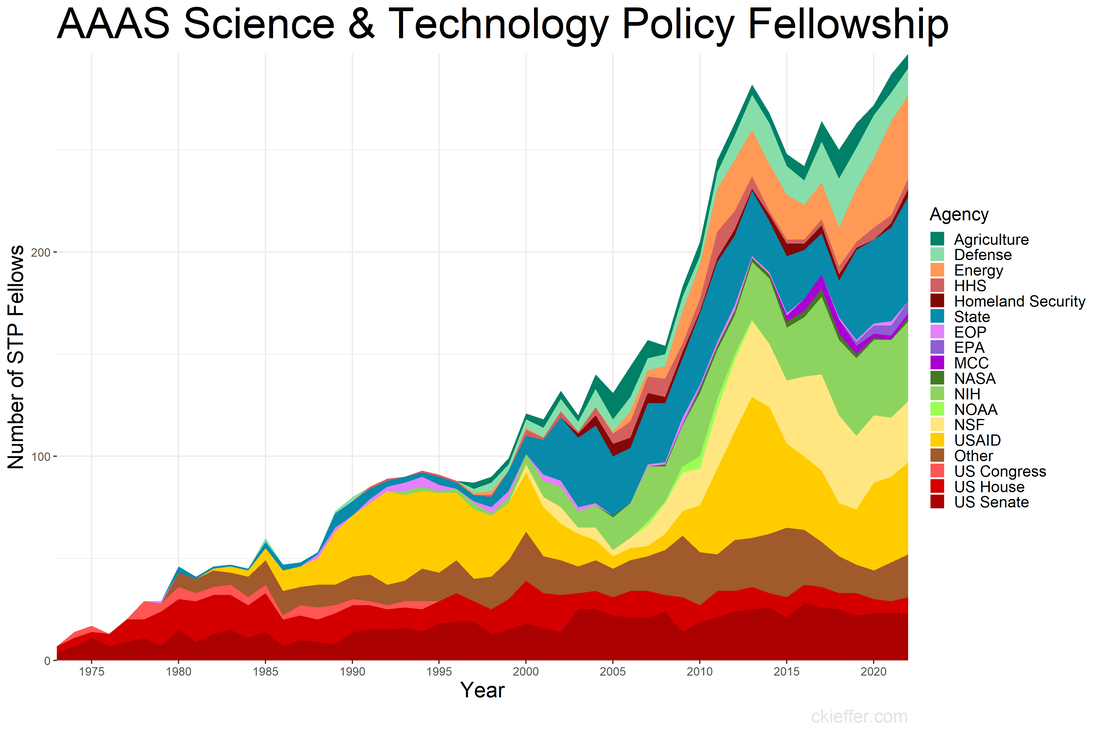

Back in January of 2020, when I was a brand-new AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow (STPF), I wrote a blog post centered around a plot of the history of the STPF. That figure contained data from all the way back in 1973 through 2019. Today’s post is an updated revisit to that post using the most recent trends in the fellowship. If you’re curious about the history of the AAAS STPF, I recommend checking out this timeline on their website and revisiting the previous version of this figure. Here’s the updated figure: One major event has happened since the last update: the COVID-19 pandemic. This has not appeared to have had a dramatic affect on the trends in 2020 or after. In fact, the fellowship has recovered well following the pandemic with a record high number of fellows in 2022 (297). This was driven in part by increases in the number of fellows at State, USAID, and in “Other” agencies in the past three years. Since the previous analysis, three new agencies have received fellows for the first time: the Department of the Treasury, the Architect of the Capitol, and AAAS itself.

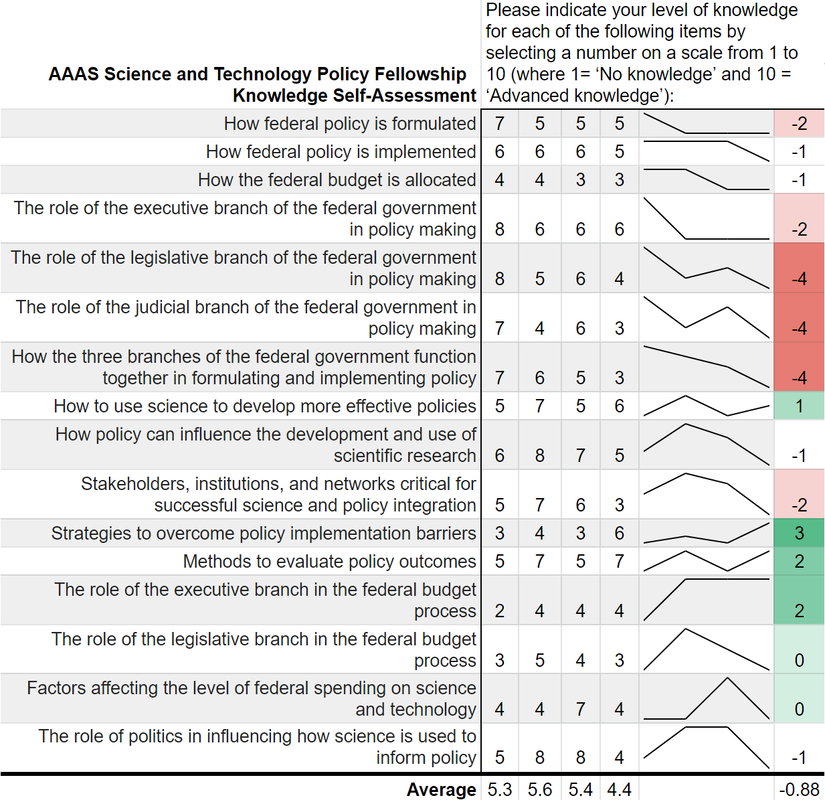

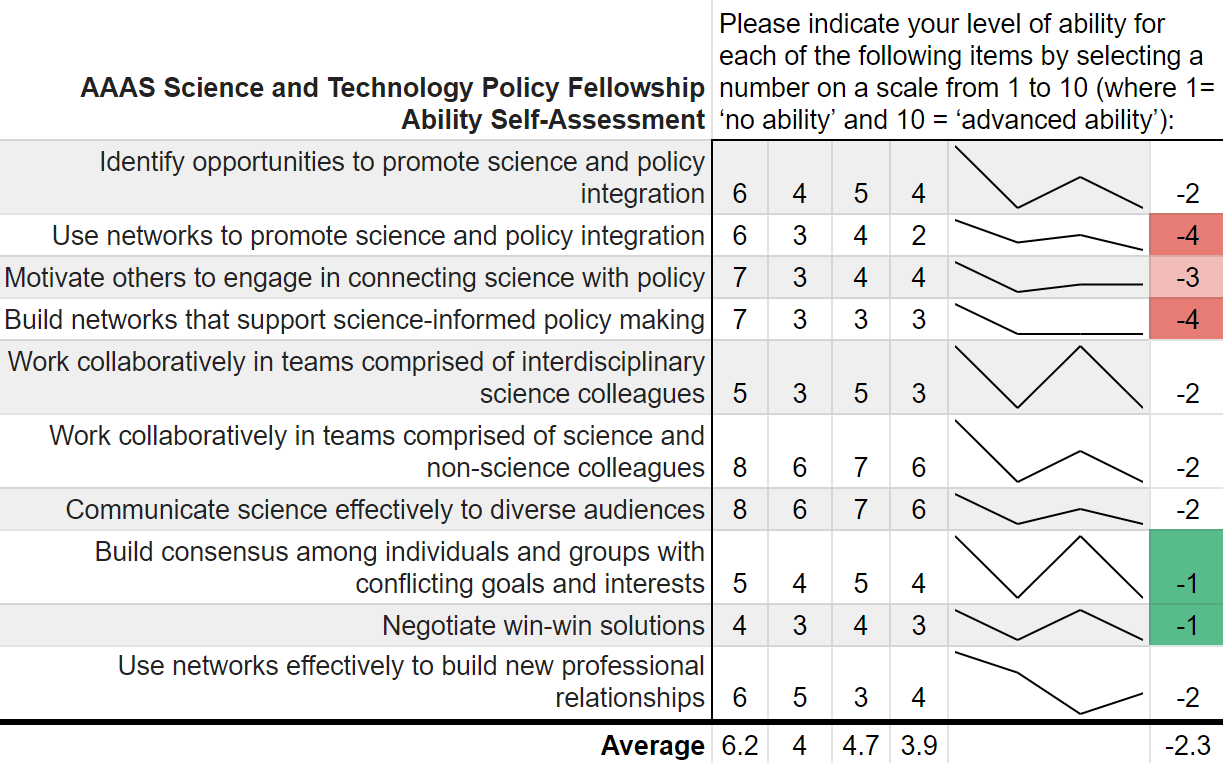

The AAAS STPF appears to be on an upward and healthy trajectory, unhindered by the global pandemic or any of our other global crises. One former fellow asked to comment on the updated figure said, "it shows the continued importance of science that drives solutions to global crises." Well said. Coda: This is a quick post to update the trends. If nothing else, it keeps my R skills up to date and gives the new fellows the lay of the land. Since that original post, I've written two other AAAS STPF-themed posts on placement office retention and my own knowledge gained through the fellowship. Check those out to learn more about the fellowship. “Can you teach an old scientist new tricks?” is a question that you have likely never asked yourself. But if you think about it, presumably, scientists should be adept at absorbing new information and then adjusting their world view accordingly. However, does that hold for non-science topics such as federal policy making? More and more the United States needs scientists who have non-science skills in order to make tangible advancements on topics such as climate change, space exploration, biological weapons, and the opioid crisis. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellowship (STPF) helps to meet that need for scientists in government as well as to teach scientists the skills they need to succeed in policymaking. As the United States’ preeminent science policy fellowship, the AAAS STPF places doctoral-level scientists in the federal government to increase evidence-informed practices across government. In 2019, the program placed 268 scientists in 21 different federal agencies. Beyond simply lending some brilliant brains to the government, the AAAS STPF is a professional development program meant to benefit the scientist as much as the hosting agency. In addition to hands-on experience in government, fellows create individual development plans, attend professional development programming, start affinity groups, and spend program development funds. As part of its monitoring and evaluation of the learning in their program, AAAS sends out a biannual survey—that is, two times per year—to fellows to monitor changes in knowledge and ability, among other things. Now, as a spoiler, I was a AAAS STPF from 2019-2021 and I am sharing some of my survey results below, presented in the most compelling data visual medium—screenshots of spreadsheets. Each of the four columns represents on of the biannual surveys. Let's see how much I learned: Um, where is the learning? Starting with my knowledge self-assessment, the outcomes are, at first blush, resoundingly negative. The average scores were lowest in the final evaluation of my fellowship (4.4 points) with an average fellowship-long change of -0.88 points. I was particularly bullish on my confidence in understanding each branch’s contribution policy making at the beginning of the fellowship and incredibly unsure of how policy was made at the close of the fellowship. There is however, one positive cluster of green boxes. These seem to focus more on learning about the budget, which I initially knew nothing about. Also, the positive items—with terms like “strategies” and “methods”--are more tangible and action focused. This would seem to support the value of the hands on experience compared to some of the more abstract concepts of how the government at large works. While not a glowing assessment of the program, let’s move on to the ability self-assessment… Yikes; that's even worse! There isn’t a single positive score differential on my ability self-assessment across the two years. Did I truly learn nothing? While the knowledge self-assessment had a small average point decline across the two years of the fellowship (0.9 points), the ability self-assessment had a larger average decline of 2.3 points. This decline was largest in my perceived ability to use and build networks. The working hypothesis to explain this discrepancy is, what else, the COVID-19 global pandemic. This dramatically reduced the ability to meet in groups and collaborate, something that many of these ability questions focus on. My responses here also had more noise and fewer clear trends compared to the knowledge self-assessment.

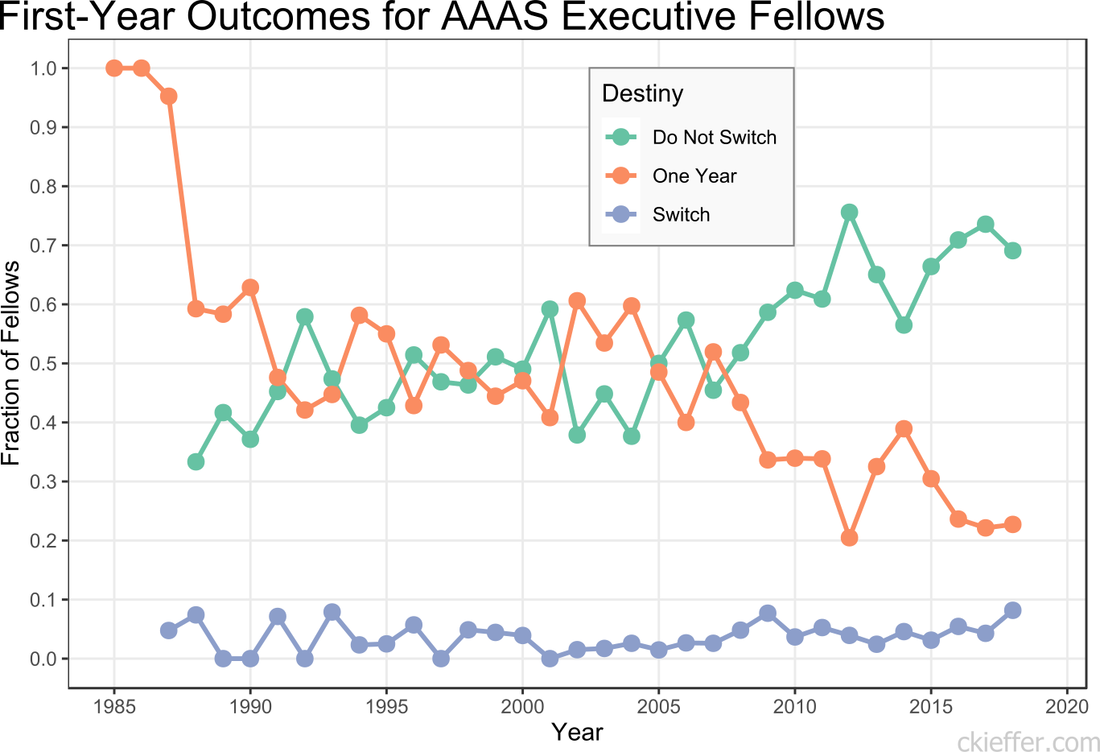

While COVID-19 likely played some role, both parts of the survey suffer from a pronounced Dunning-Kruger effect. Before the program I read the news, had taken AP Government, and had seen SchoolHouse Rock. Apparently, I thought that was sufficient to make me well-informed. This was a bold opinion considering that I was not 100% sure what the State Department did. After some practical experience in government, I slowly understood the complexities of the interconnected systems. Rather, I should say that I did not understand the labyrinthine bureaucracies, but at least began to appreciate their magnitude. That appreciation is what contributed to the decrease in survey scores over time. Not a lack of learning, but instead the learning of hidden truths juxtaposed with my initial ignorance. Despite these survey data, the AAAS STPF has taught me a tremendous amount about the federal government, policy making, and science’s role in that process. The first question on the survey is “Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience as a AAAS Science & Technology Policy fellow?” which I consistently rated as “Very Satisfied.” Increasingly, more and more fellows are remaining in the same office for a second year, indicating a high level of program satisfaction. The number reupping now sits around 70%. Finally, this is only a single data point from me. I did not ask AAAS for their data, but I have a sneaking suspicion that would be reluctant to part with it. Therefore, it is possible that no other fellows have this problem. Every other fellow is completely clear eyed and knows the truth about both themselves and the U.S. government. But if that was the case, then we wouldn’t need the AAAS STPF at all. I am glad that I learned what I didn’t know. Now I am off to learn my next trick. Previously, I presented information on the agency composition over time of American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellows (STPF). This analysis was based on the data collected from the publicly available database of AAAS fellows. The goal of the program is to place Ph.D.-level scientists into the federal government to broadly increase science- and evidence-based policy. The STPF program consists of both executive and legislative branch fellows. Executive branch fellows enter into a one-year fellowship, with the option to extend their fellowship after their first year. Additionally, fellows can reapply to transition their fellowship to other offices around the federal government. To extend my previous analysis, I re-analyzed the data to discover the "destiny" of first-year fellows. How many fellows chose to stay in the same agency after their first year, leave the program, or switch agencies? The number of fellows that “Do Not Switch” and remain in the same office for both years, has been trending upwards over time. Over the past five years, on average, 67.3 percent of fellows completed both years of their fellowship in the same agency. The remaining 32.7 percent either left after the first year or switched to a different agency. Reasons for this increasing trend are not discernible from the data. More and more offices (or even fellows) may be treating this as a full two-year fellowship rather than a one-and-one. Early executive branch fellows only had a one-year fellowship, leading to the dramatic 100 percent program exit after a single year. Historically, the percentage of executive branch fellows who switch offices between their first and second years has been low and has never exceeded nine percent. However, the year with the largest number of switches was recent. The largest total number of switches was by fellows who began their first year in 2018, nine (8.1 percent) switched agencies. That year, six of the nine fellows who switched departments moved into the Department of State. The largest number of one-year switches out of a single agency was four. The data were not analyzed for office switches within the same agency and only inter-agency transfers are recorded as changes. This may lead to under-reporting of position switches. Additionally, some fellows who leave the STPF program after their first year may have received full-time positions at their host agency. While they are no longer fellows, they did not actually leave leave their agency and conceivably could have stayed for a second year of the STPF program there. Unlike the executive branch fellowship, AAAS’s legislative branch fellowship is only a one-year program. However, some legislative branch fellows apply for, and eventually receive, executive branch fellowships. Over the history of the fellowship program 106 fellows have moved directly from congress into an executive branch fellowship the following year. This is out of the total 1,399 congressional fellows. The previous five-year average for fellows moving from The Hill to the executive branch is 7.2 fellows per year or 36 total fellows in the past five years. Overall, it appears that the AAAS STPF program’s opaque agency-fellow matching process is doing an increasingly good job of helping fellows find agencies where they are happy to live out the full two years of their executive branch fellowship experience. In these “strange times,” running has become a lifeline to the outdoors. It is one of the few legitimate excuses to venture outside of my efficiently-sized apartment. I started running in graduate school to manage stress and, even as my physical body continues to deteriorate, I continue to use running to shore up my mental stability. As the severity of the COVID-19 situation raises the stress floor across the nation, maintaining--or even developing--a simple running routine is restorative. I use the Strava phone app to track my runs. This app records times and distance traveled which is posted to a social-media-esque timeline for others to see. I choose this app after very little market research, but it seems to function well most of the time and is popular enough that many of my friends also use it. My favorite feature of the app is the post-run map. At the end of each session, it shows a little map collected via GPS coordinates throughout my jog. This feature is not without its flaws. In 2018, Strava published a heatmap of all its users’ data, which included routes mapping overseas US military bases. Publishing your current location data is a huge operational security (OPSEC) violation. Strangers could easily identify your common routes and even get a good idea of where you live. I recommend updating your privacy settings to only show runs to confirmed friends. With all that said, I wanted to create my own OPSEC-violating heatmap. Essentially, can I plot all of the routes that I have run in the past 18 months on a single map? Yes! Thanks to the regulations in Europe’s GDPR, many apps have made all your data available to you, the person who actually created the data. This includes Strava, which allows you to export your entire account. It is your data so you should have access to it. If you use Strava, it is simple to download all of your information. Just login to your account via a web browser, go to settings, then my account, and, under “Download or Delete Your Account,” select “Get Started.” Strava will email you a .zip folder with all of your information. This folder is chock full of all kinds of goodies, but the real nuggets are in the “activities” folder. Here you will find a list of files with 10-digit names, each one representing an activity. You did all of these! These files are stored in the GPS Exchange (GPX) file format, which tracks your run as a sequence of points. The latitude and longitude points are coupled with both the time and elevation at that point. Strava uses this raw information to calculate all your run statistics! With this data an enterprising young developer could make their own run-tracking application. But that’s not me. Instead, I am doing much simpler: plotting the routes simultaneously on a single map. Here is what that looks like: Again, this is a huge OPSEC violation so please do not be creepy. However, the routes are repetitive enough that it is not too revealing. Each red line represents a route that I ran. Each line is 80% transparent, so lighter pink lines were run less frequently than darker red lines. You can see that I run through East Potomac Park frequently. Massachusetts Avenue is a huge thoroughfare as well. I focused the map on the downtown Washington D.C. area. I used the SP and OpenStreetMap packages in R for plotting.

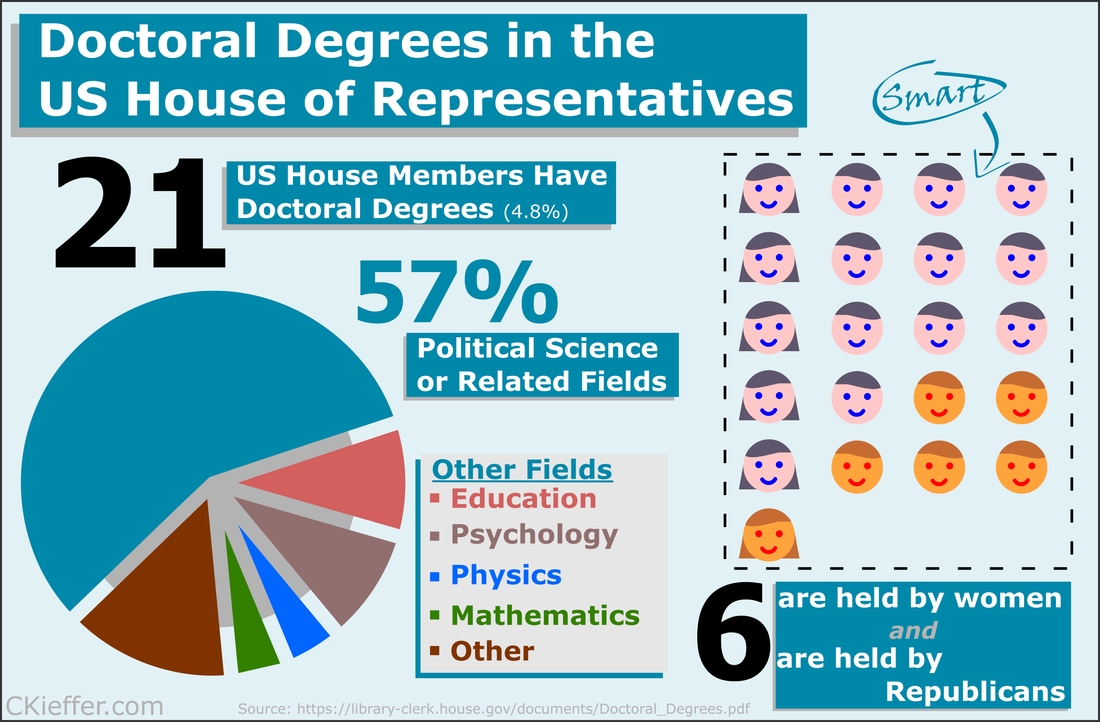

The well-tread paths on the map are not really surprising, but it does give me some ideas for ways to expand my route repertoire. My runs are centered tightly around the National Mall. I need to give SW and NE DC a little more love. I should also do some runs in Rosslyn (but the hills) or try to head south towards the airport on the Virginia side of the river. What did we learn from this exercise? Very little. This is an example of using a person’s own available data. What other websites also allow total data downloads? How can that data be visualized? Make yourself aware of where your data exists in the digital world and, if you can, use that data to learn something about your real world. My R code is available on GitHub. Note: Eagle-eyed readers may be able to identify a route where I walked across water. Is this an error or am I the second-coming? Who can say? Recently at brunch someone made a statement about there being only one person with a PhD in the US House of Representatives. This did not seem probable to me and after some Googling, I found that the House Library conveniently maintains a list of doctoral degree holders in the 116th House. Though there is only one hard science PhD in the house (Bill Foster, D-IL; Physics), there are also other STEM doctorate holders in the House including two psychologists, a mathematician, and a monogastric nutritionist. There are also obviously quite a few other doctorate holders, most of which are in political science (obviously), but also a Doctor of Ministry from Alabama (Guess the political party!).

Overall 21 is a small fraction of the House (only 4.8%), especially compared to the 157 members that are lawyers. Given the wide-reaching and technical nature of the government and the laws that regulate it, it may be advantageous to increase the number of scientists represented in Congress. While that is a decision ultimately for each state's voters, there are a number of programs aimed at increasing the involvement of scientists in government policy. As an infographic making exercise I would consider this a mixed success. I think it conveys the information effectively, but lacks a certain je ne sai quoi in the aesthetics department. My little emoji heads especially could use some work. Any graphic designers out there please reach out with tips. The House Library maintains lists of lawyers, military service members, medical professionals, as well as other specialties in their membership profile. I am going to download these lists as a baseline for the analysis of future Congresses. |

Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed