|

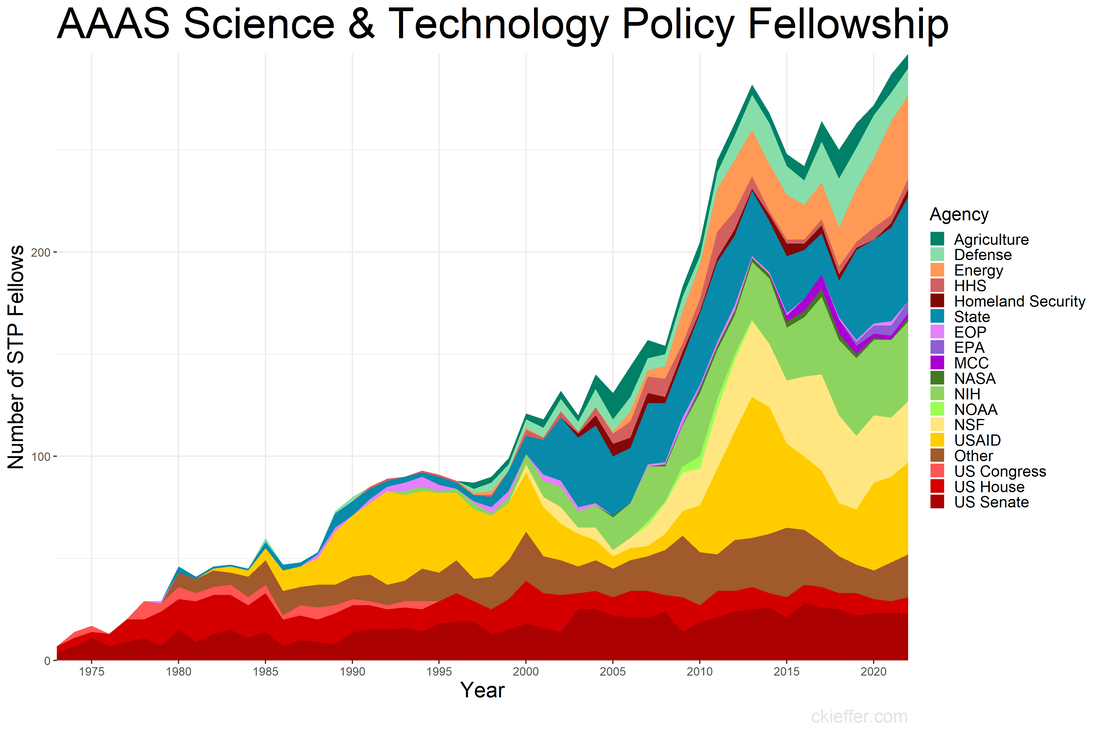

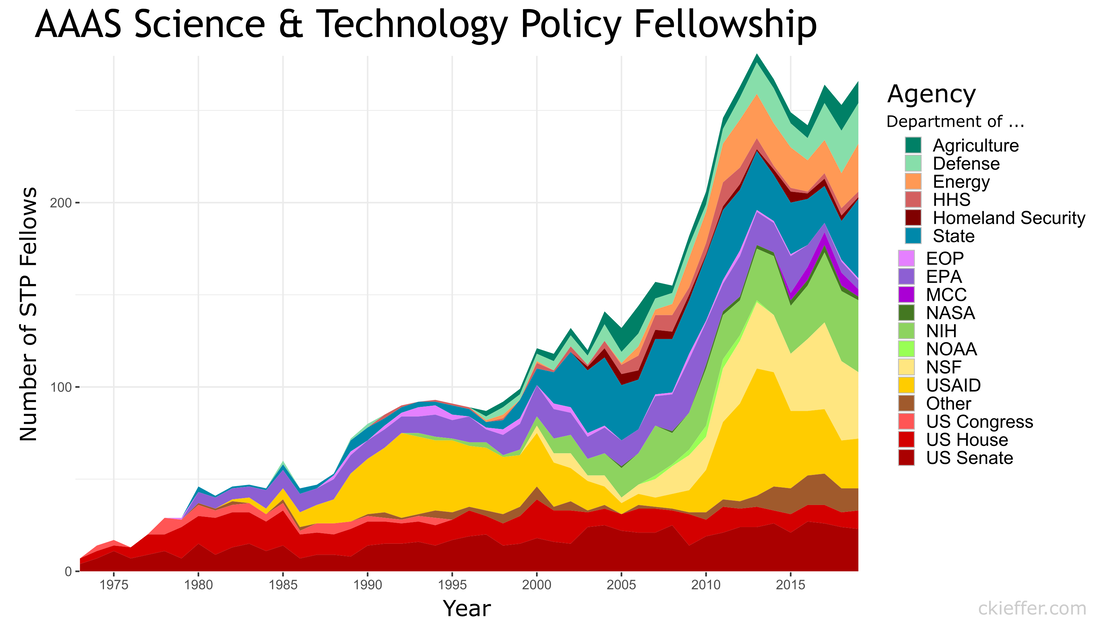

Back in January of 2020, when I was a brand-new AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow (STPF), I wrote a blog post centered around a plot of the history of the STPF. That figure contained data from all the way back in 1973 through 2019. Today’s post is an updated revisit to that post using the most recent trends in the fellowship. If you’re curious about the history of the AAAS STPF, I recommend checking out this timeline on their website and revisiting the previous version of this figure. Here’s the updated figure: One major event has happened since the last update: the COVID-19 pandemic. This has not appeared to have had a dramatic affect on the trends in 2020 or after. In fact, the fellowship has recovered well following the pandemic with a record high number of fellows in 2022 (297). This was driven in part by increases in the number of fellows at State, USAID, and in “Other” agencies in the past three years. Since the previous analysis, three new agencies have received fellows for the first time: the Department of the Treasury, the Architect of the Capitol, and AAAS itself.

The AAAS STPF appears to be on an upward and healthy trajectory, unhindered by the global pandemic or any of our other global crises. One former fellow asked to comment on the updated figure said, "it shows the continued importance of science that drives solutions to global crises." Well said. Coda: This is a quick post to update the trends. If nothing else, it keeps my R skills up to date and gives the new fellows the lay of the land. Since that original post, I've written two other AAAS STPF-themed posts on placement office retention and my own knowledge gained through the fellowship. Check those out to learn more about the fellowship.

0 Comments

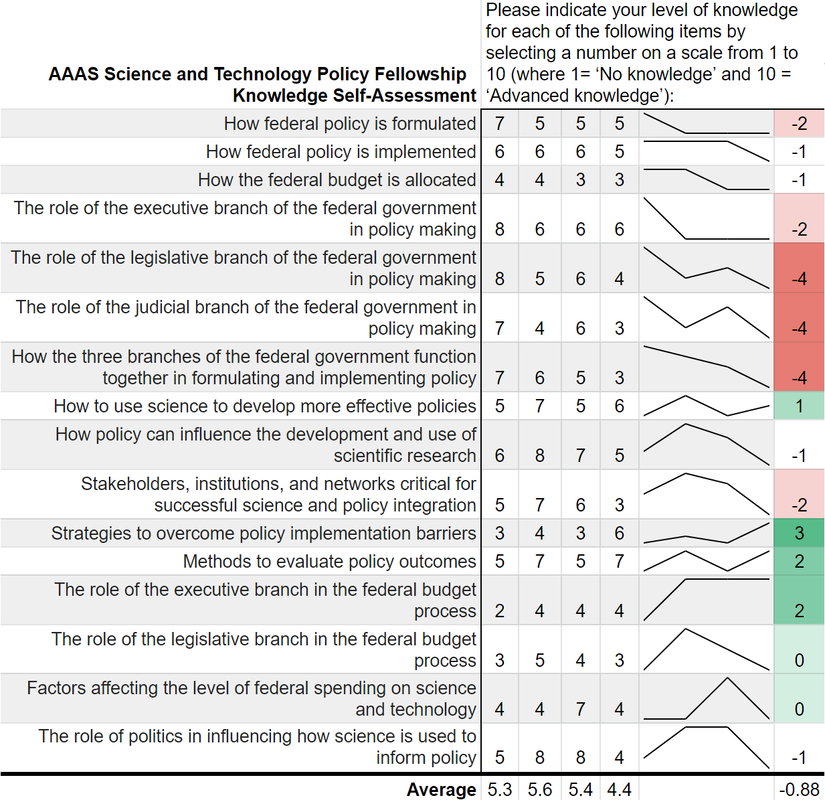

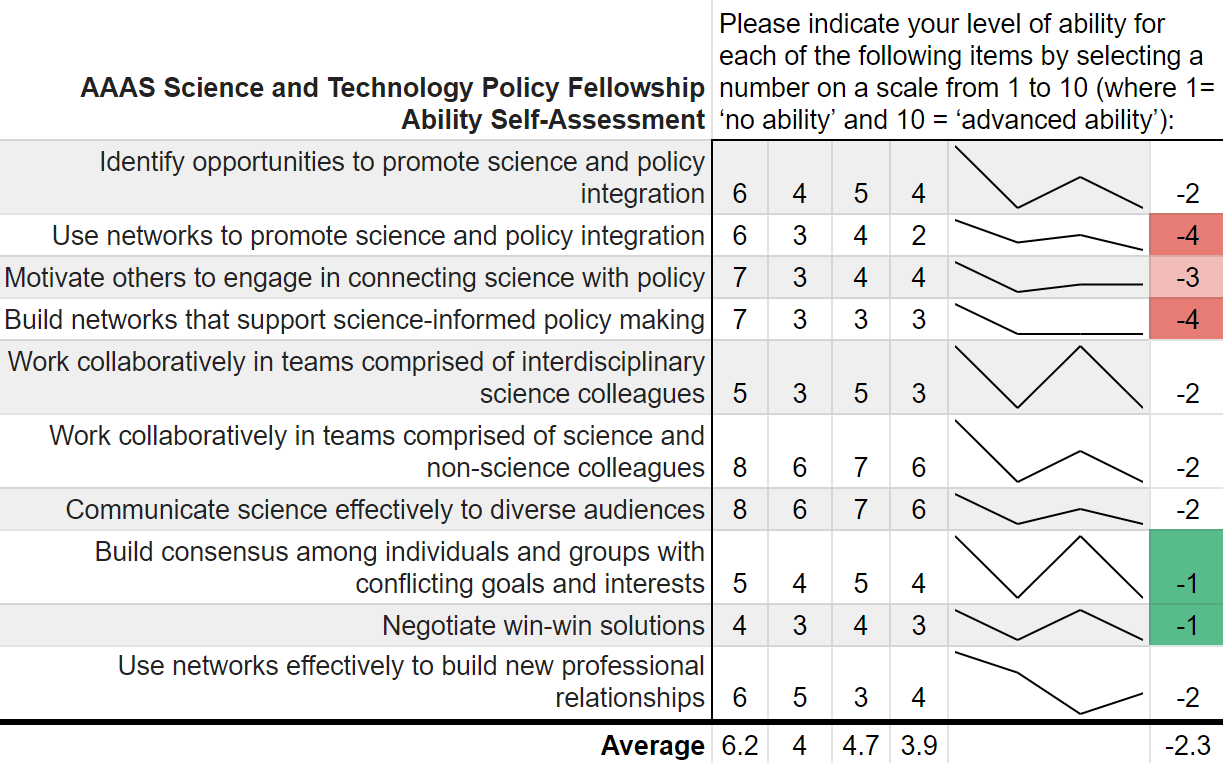

“Can you teach an old scientist new tricks?” is a question that you have likely never asked yourself. But if you think about it, presumably, scientists should be adept at absorbing new information and then adjusting their world view accordingly. However, does that hold for non-science topics such as federal policy making? More and more the United States needs scientists who have non-science skills in order to make tangible advancements on topics such as climate change, space exploration, biological weapons, and the opioid crisis. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellowship (STPF) helps to meet that need for scientists in government as well as to teach scientists the skills they need to succeed in policymaking. As the United States’ preeminent science policy fellowship, the AAAS STPF places doctoral-level scientists in the federal government to increase evidence-informed practices across government. In 2019, the program placed 268 scientists in 21 different federal agencies. Beyond simply lending some brilliant brains to the government, the AAAS STPF is a professional development program meant to benefit the scientist as much as the hosting agency. In addition to hands-on experience in government, fellows create individual development plans, attend professional development programming, start affinity groups, and spend program development funds. As part of its monitoring and evaluation of the learning in their program, AAAS sends out a biannual survey—that is, two times per year—to fellows to monitor changes in knowledge and ability, among other things. Now, as a spoiler, I was a AAAS STPF from 2019-2021 and I am sharing some of my survey results below, presented in the most compelling data visual medium—screenshots of spreadsheets. Each of the four columns represents on of the biannual surveys. Let's see how much I learned: Um, where is the learning? Starting with my knowledge self-assessment, the outcomes are, at first blush, resoundingly negative. The average scores were lowest in the final evaluation of my fellowship (4.4 points) with an average fellowship-long change of -0.88 points. I was particularly bullish on my confidence in understanding each branch’s contribution policy making at the beginning of the fellowship and incredibly unsure of how policy was made at the close of the fellowship. There is however, one positive cluster of green boxes. These seem to focus more on learning about the budget, which I initially knew nothing about. Also, the positive items—with terms like “strategies” and “methods”--are more tangible and action focused. This would seem to support the value of the hands on experience compared to some of the more abstract concepts of how the government at large works. While not a glowing assessment of the program, let’s move on to the ability self-assessment… Yikes; that's even worse! There isn’t a single positive score differential on my ability self-assessment across the two years. Did I truly learn nothing? While the knowledge self-assessment had a small average point decline across the two years of the fellowship (0.9 points), the ability self-assessment had a larger average decline of 2.3 points. This decline was largest in my perceived ability to use and build networks. The working hypothesis to explain this discrepancy is, what else, the COVID-19 global pandemic. This dramatically reduced the ability to meet in groups and collaborate, something that many of these ability questions focus on. My responses here also had more noise and fewer clear trends compared to the knowledge self-assessment.

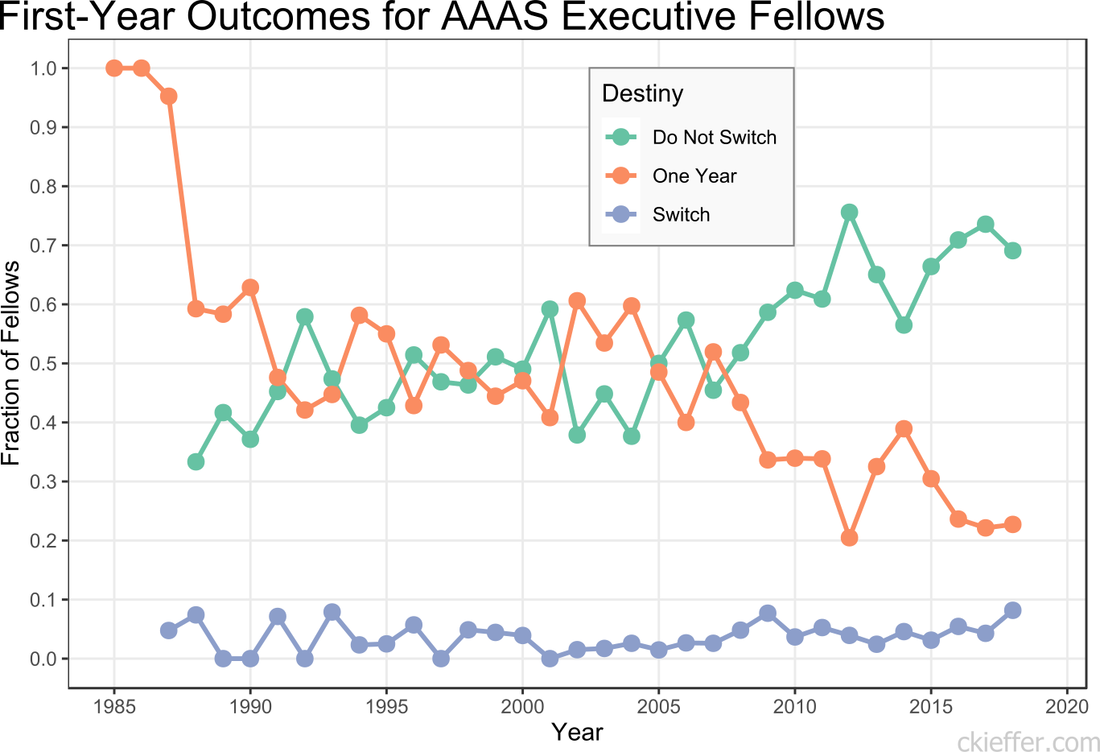

While COVID-19 likely played some role, both parts of the survey suffer from a pronounced Dunning-Kruger effect. Before the program I read the news, had taken AP Government, and had seen SchoolHouse Rock. Apparently, I thought that was sufficient to make me well-informed. This was a bold opinion considering that I was not 100% sure what the State Department did. After some practical experience in government, I slowly understood the complexities of the interconnected systems. Rather, I should say that I did not understand the labyrinthine bureaucracies, but at least began to appreciate their magnitude. That appreciation is what contributed to the decrease in survey scores over time. Not a lack of learning, but instead the learning of hidden truths juxtaposed with my initial ignorance. Despite these survey data, the AAAS STPF has taught me a tremendous amount about the federal government, policy making, and science’s role in that process. The first question on the survey is “Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience as a AAAS Science & Technology Policy fellow?” which I consistently rated as “Very Satisfied.” Increasingly, more and more fellows are remaining in the same office for a second year, indicating a high level of program satisfaction. The number reupping now sits around 70%. Finally, this is only a single data point from me. I did not ask AAAS for their data, but I have a sneaking suspicion that would be reluctant to part with it. Therefore, it is possible that no other fellows have this problem. Every other fellow is completely clear eyed and knows the truth about both themselves and the U.S. government. But if that was the case, then we wouldn’t need the AAAS STPF at all. I am glad that I learned what I didn’t know. Now I am off to learn my next trick. Previously, I presented information on the agency composition over time of American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellows (STPF). This analysis was based on the data collected from the publicly available database of AAAS fellows. The goal of the program is to place Ph.D.-level scientists into the federal government to broadly increase science- and evidence-based policy. The STPF program consists of both executive and legislative branch fellows. Executive branch fellows enter into a one-year fellowship, with the option to extend their fellowship after their first year. Additionally, fellows can reapply to transition their fellowship to other offices around the federal government. To extend my previous analysis, I re-analyzed the data to discover the "destiny" of first-year fellows. How many fellows chose to stay in the same agency after their first year, leave the program, or switch agencies? The number of fellows that “Do Not Switch” and remain in the same office for both years, has been trending upwards over time. Over the past five years, on average, 67.3 percent of fellows completed both years of their fellowship in the same agency. The remaining 32.7 percent either left after the first year or switched to a different agency. Reasons for this increasing trend are not discernible from the data. More and more offices (or even fellows) may be treating this as a full two-year fellowship rather than a one-and-one. Early executive branch fellows only had a one-year fellowship, leading to the dramatic 100 percent program exit after a single year. Historically, the percentage of executive branch fellows who switch offices between their first and second years has been low and has never exceeded nine percent. However, the year with the largest number of switches was recent. The largest total number of switches was by fellows who began their first year in 2018, nine (8.1 percent) switched agencies. That year, six of the nine fellows who switched departments moved into the Department of State. The largest number of one-year switches out of a single agency was four. The data were not analyzed for office switches within the same agency and only inter-agency transfers are recorded as changes. This may lead to under-reporting of position switches. Additionally, some fellows who leave the STPF program after their first year may have received full-time positions at their host agency. While they are no longer fellows, they did not actually leave leave their agency and conceivably could have stayed for a second year of the STPF program there. Unlike the executive branch fellowship, AAAS’s legislative branch fellowship is only a one-year program. However, some legislative branch fellows apply for, and eventually receive, executive branch fellowships. Over the history of the fellowship program 106 fellows have moved directly from congress into an executive branch fellowship the following year. This is out of the total 1,399 congressional fellows. The previous five-year average for fellows moving from The Hill to the executive branch is 7.2 fellows per year or 36 total fellows in the past five years. Overall, it appears that the AAAS STPF program’s opaque agency-fellow matching process is doing an increasingly good job of helping fellows find agencies where they are happy to live out the full two years of their executive branch fellowship experience. Since 1973, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) has facilitated the Science & Technology Policy fellowship (STPF). The goal of the program is to infuse scientific thinking into the political decision making process, as well as developing a workforce that is knowledgeable in both policymaking and science. Intuitively, it makes sense to place evidence-focused scientists in the government to support key decisions makers. Each year doctoral-level scientists are placed throughout the federal government for one to two year fellowships. Initially the program placed scientists exclusively in the Legislative branch, but as the program grew, placements in the Executive branch became more common. In 2019, hundreds of scientists were placed in 21 different agencies throughout the federal government. As one of those fellows, I wanted to create a Microsoft Excel-based directory of current fellows. However, what began as a project to develop a simple CSV file turned into a visual exploration of the historic and current composition of the AAAS STPF program. Below are some of my observations. Data was collected from the publicly available Fellow Directory. In the beginning of the STPF program, 100% of fellows were placed in the Legislative Branch. This continued until the first Executive branch fellows around 1980 were placed in the State Department, Executive Office of the President (EOP), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In 1986, the number of Executive Branch fellows overtook the number of Legislative Branch Fellows for the first time. Since those initial Executive Branch placements, fellows have found homes in 43 different organizations. The U.S. Senate has had the largest total number of fellows while the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is the Executive Branch agency that has had the most placements. Unfortunately, for the clarity of the figure, agencies with fewer than twenty total fellow placements were grouped into a single "other" category. Despite the mundane label, this category represents strength and diversity of the AAAS STPF. The "other" category encompasses 25 different agencies including the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the World Bank, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the RAND Corporation. In 2017, fellows were placed in 24 different organizations, the most diverse of any year. The total number of fellows has dramatically increased over the past 45 years (as seen in the grey bar plot at the bottom of the figure). The initial cohort of congressional fellows in 1973 had just seven enterprising scientists. Compare that to 2013 when a total of 282 fellows were selected and placed. This year (2019) tied 2014 for the second highest number of placements with 268 fellows. One of the most striking observations is the trends in placement at USAID. In 1982 USAID began to sponsor AAAS Executive Branch fellows, with one placement. Placements at USAID quickly grew, ballooning to over 50% of total fellow placements in 1992. However, just as rapidly, the placement fraction at USAID decreased during the 2000s despite only a small increase in the overall number of fellows. This trend ultimately began to reverse in 2010, and a large increase in the total number of fellows found placement opportunities at USAID. The reader is left to craft their own explanatory narrative. One thing is clear from the data: the AAAS STPF is as strong as it has ever been. Placement numbers are close to all-time highs and fellows are represented at a robust number of agencies. Only time will tell if the experience these fellows gain will help them achieve the program's mission "to develop and execute solutions to address societal challenges." If you want to learn more about the history of the STPF, including statistics for each class, AAAS has an interactive timeline on their website. An unexpected surprise during the analysis was the discovery that Dr. Rodney McKay and John Sheppard (both of Stargate Atlantis fame) were STP fellows. Or--more likely--the developer for the Fellows Directory was a fan of the show. Unfortunately, as a Canadian citizen, Dr. McKay would be ineligible for the AAAS STPF.

|

Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed