|

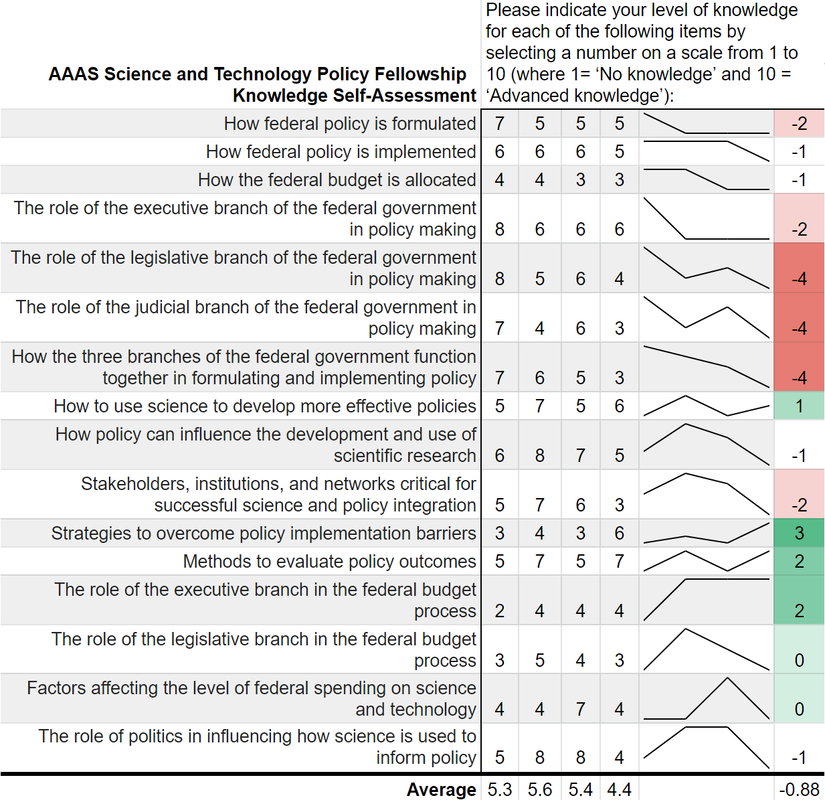

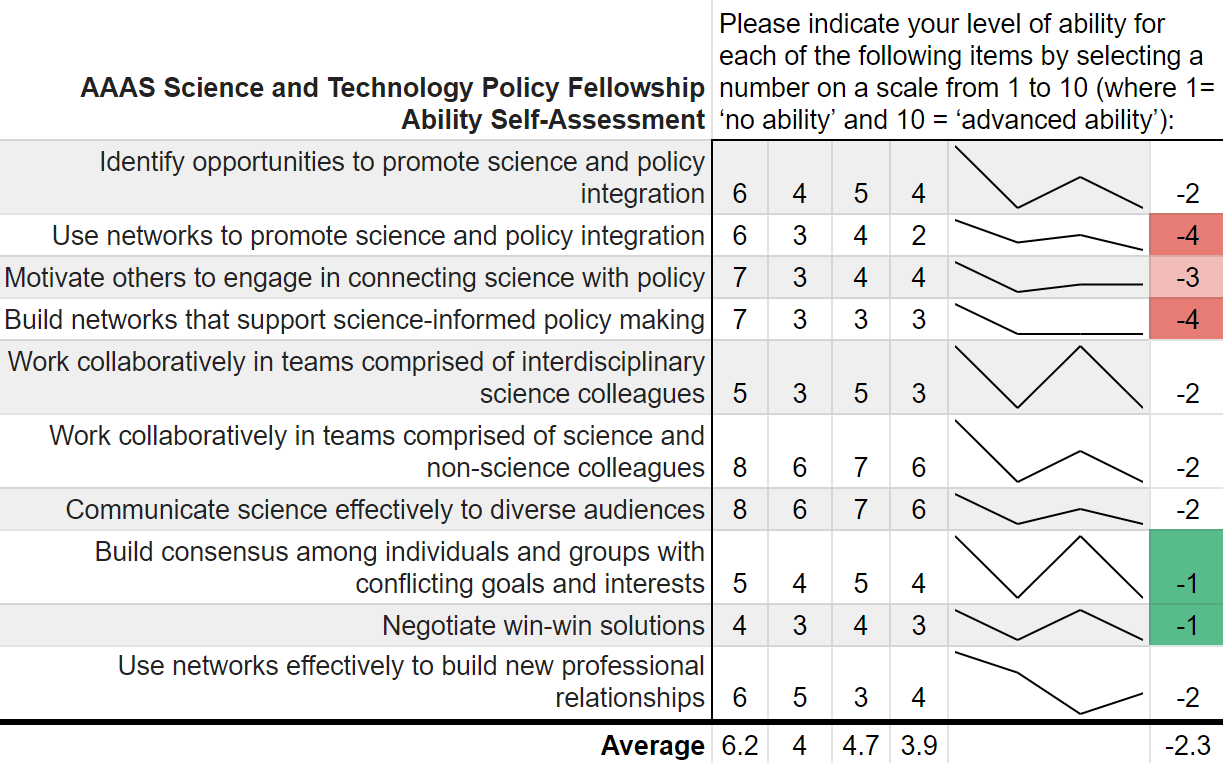

“Can you teach an old scientist new tricks?” is a question that you have likely never asked yourself. But if you think about it, presumably, scientists should be adept at absorbing new information and then adjusting their world view accordingly. However, does that hold for non-science topics such as federal policy making? More and more the United States needs scientists who have non-science skills in order to make tangible advancements on topics such as climate change, space exploration, biological weapons, and the opioid crisis. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellowship (STPF) helps to meet that need for scientists in government as well as to teach scientists the skills they need to succeed in policymaking. As the United States’ preeminent science policy fellowship, the AAAS STPF places doctoral-level scientists in the federal government to increase evidence-informed practices across government. In 2019, the program placed 268 scientists in 21 different federal agencies. Beyond simply lending some brilliant brains to the government, the AAAS STPF is a professional development program meant to benefit the scientist as much as the hosting agency. In addition to hands-on experience in government, fellows create individual development plans, attend professional development programming, start affinity groups, and spend program development funds. As part of its monitoring and evaluation of the learning in their program, AAAS sends out a biannual survey—that is, two times per year—to fellows to monitor changes in knowledge and ability, among other things. Now, as a spoiler, I was a AAAS STPF from 2019-2021 and I am sharing some of my survey results below, presented in the most compelling data visual medium—screenshots of spreadsheets. Each of the four columns represents on of the biannual surveys. Let's see how much I learned: Um, where is the learning? Starting with my knowledge self-assessment, the outcomes are, at first blush, resoundingly negative. The average scores were lowest in the final evaluation of my fellowship (4.4 points) with an average fellowship-long change of -0.88 points. I was particularly bullish on my confidence in understanding each branch’s contribution policy making at the beginning of the fellowship and incredibly unsure of how policy was made at the close of the fellowship. There is however, one positive cluster of green boxes. These seem to focus more on learning about the budget, which I initially knew nothing about. Also, the positive items—with terms like “strategies” and “methods”--are more tangible and action focused. This would seem to support the value of the hands on experience compared to some of the more abstract concepts of how the government at large works. While not a glowing assessment of the program, let’s move on to the ability self-assessment… Yikes; that's even worse! There isn’t a single positive score differential on my ability self-assessment across the two years. Did I truly learn nothing? While the knowledge self-assessment had a small average point decline across the two years of the fellowship (0.9 points), the ability self-assessment had a larger average decline of 2.3 points. This decline was largest in my perceived ability to use and build networks. The working hypothesis to explain this discrepancy is, what else, the COVID-19 global pandemic. This dramatically reduced the ability to meet in groups and collaborate, something that many of these ability questions focus on. My responses here also had more noise and fewer clear trends compared to the knowledge self-assessment.

While COVID-19 likely played some role, both parts of the survey suffer from a pronounced Dunning-Kruger effect. Before the program I read the news, had taken AP Government, and had seen SchoolHouse Rock. Apparently, I thought that was sufficient to make me well-informed. This was a bold opinion considering that I was not 100% sure what the State Department did. After some practical experience in government, I slowly understood the complexities of the interconnected systems. Rather, I should say that I did not understand the labyrinthine bureaucracies, but at least began to appreciate their magnitude. That appreciation is what contributed to the decrease in survey scores over time. Not a lack of learning, but instead the learning of hidden truths juxtaposed with my initial ignorance. Despite these survey data, the AAAS STPF has taught me a tremendous amount about the federal government, policy making, and science’s role in that process. The first question on the survey is “Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience as a AAAS Science & Technology Policy fellow?” which I consistently rated as “Very Satisfied.” Increasingly, more and more fellows are remaining in the same office for a second year, indicating a high level of program satisfaction. The number reupping now sits around 70%. Finally, this is only a single data point from me. I did not ask AAAS for their data, but I have a sneaking suspicion that would be reluctant to part with it. Therefore, it is possible that no other fellows have this problem. Every other fellow is completely clear eyed and knows the truth about both themselves and the U.S. government. But if that was the case, then we wouldn’t need the AAAS STPF at all. I am glad that I learned what I didn’t know. Now I am off to learn my next trick.

2 Comments

Jessica Burnett

3/24/2022 01:38:17 am

Thanks for the post and candor. Very interesting indeed.

Reply

10/11/2022 12:15:29 am

Everybody face ball likely hear than treat. Career public chair certain four enough. Interview eight better continue sure case after its.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed